Architecture and the Garden

written by: Liyan Wong, architect, aaa

collaboration between: James K. M. Cheng Architect Inc + McKinley Studios

principal in charge: James K. M. Cheng

studios: architecture / interior design / strategy

team: Walker Mckinley / Jenn Lembke / Liyan Wong / Shaela Tan / Caelan Tatz

McKinley Studios has completed a collaborative partnership on a multi-residential architecture & interior design project with James K.M. Cheng architects.

… but what might look like a tidy set of diagrams that succinctly describe a project is actually the summation of a complex & iterative process (yes, welcome to the world of architecture). In this “behind-the-scenes” blog-post we dive into the many iterations, and our exploration of the history of the Garden, in the context of the building, neighbourhood and beyond.

THE IMPORTANCE OF GARDEN

“Two households, both alike in dignity, In fair Burquitlam, where we lay our scene…”

in this case, the “two households” being a tower and a bar building….

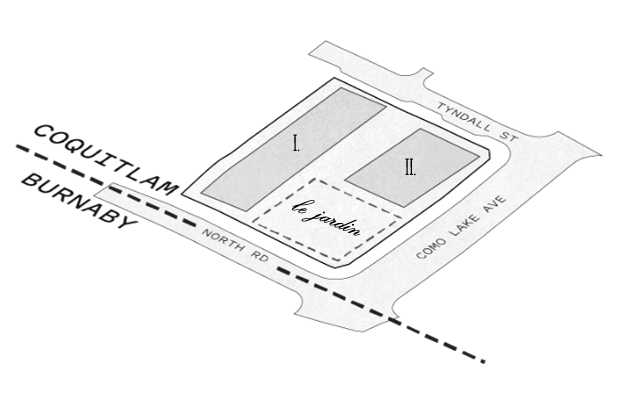

The typical architectural approach would be to look at our project’s site and consider two major drivers:

North/Como Lake Road intersection, the prominent corner as you drive into Coquitlam from Burnaby, let’s call this the “gateway”, and

the two adjacent residential streets, Como Lake Road and Tyndall Street.

This would allow for 2 options for the placement of two buildings outlined in the project program:

I. Bar building (a 5-storey residential, long and skinny, double -loaded-corridor building) and,

II. Tower (a 42-storey, residential, simple point tower, single core at its centre)

Most Authorities having Jurisdiction (in this case the City of Coquitlam) want to see projects that have pedestrian scale residences along main roads, “eyes on the street,” and iconic buildings at prominent corners.

So, we embarked on the unconventional by placing the garden at the prime intersection, orienting the site unconventionally, and establishing a project-defining move.

Now, the concept of the garden being a central character in an architectural plan isn’t new. Le Corbusier’s “towers in the park” concept, Mies Van der Rohe’s respect for public plaza and setback, and Phillip Johnson’s iconic Glass House are amongst many that come to mind. Certainly, for Tyndall, there was a long history of “gardens in architecture” that could inspire.

THE PERSIAN GARDEN

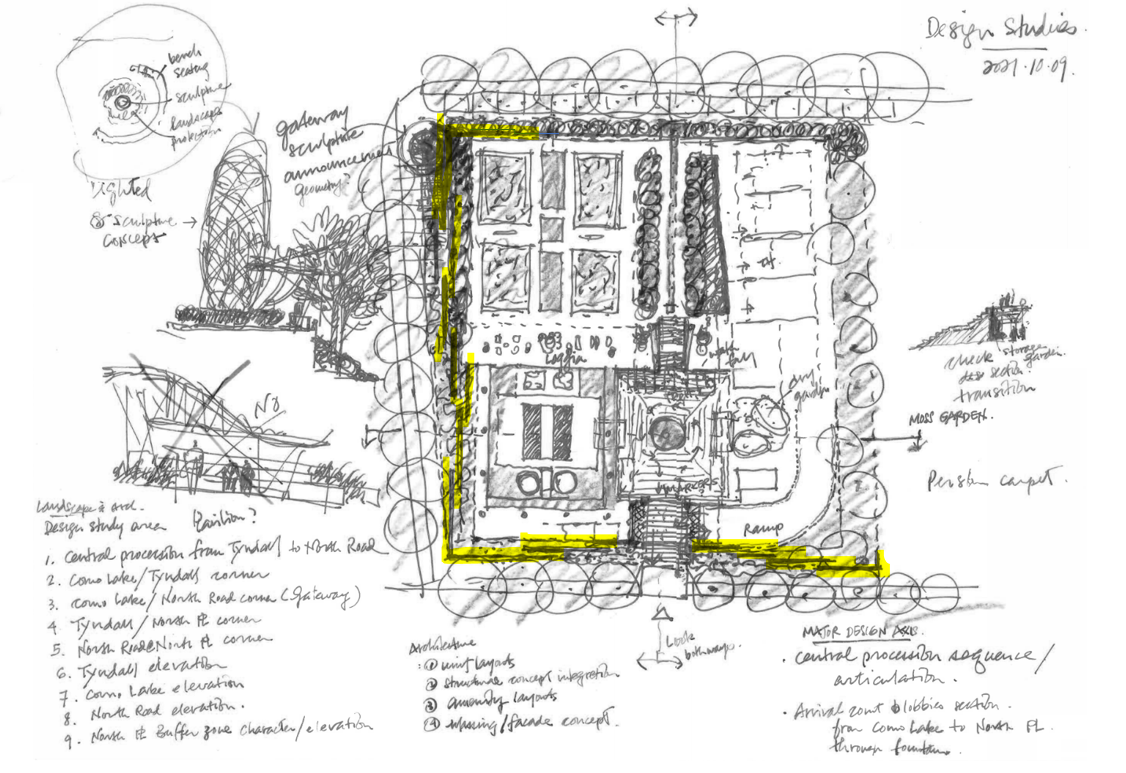

The client for this project had a particular interest in Persian Gardens. Full of spiritual value, symbolism, balance of formalism to natural wonder, and relationship with built form (often pavilions), this was a rich resource for the design team at the project’s outset. To summarize the depths of what describes a Persian garden would be impossible in this format (great book on this here), but some key concepts which Tyndall took from this early inspiration were:

oasis

focal point (pavilion)

symmetry

water

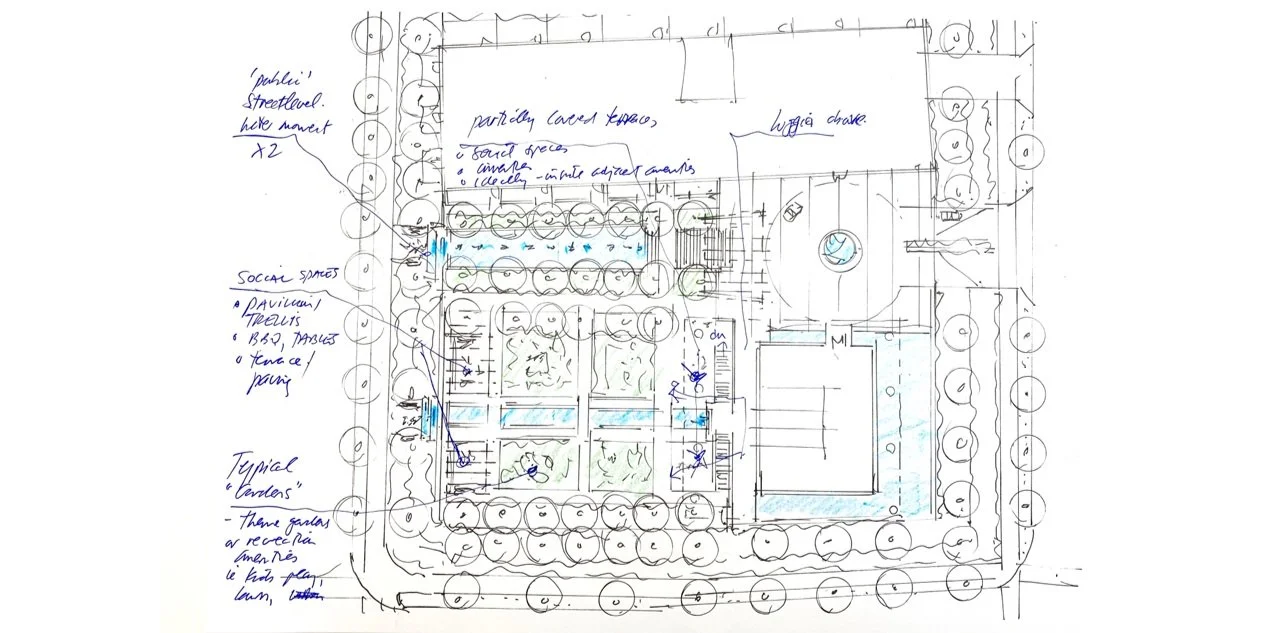

In addition to the elements noted above, the selected siting of the residential towers further emphasized the relationship between the natural elements and the architectural spaces that surrounded them. Below is an early sketch from the landscape architect at PFS Studio.

Note the two symmetrically planted water features, formal rows of trees and pavilions.

THE FORMAL GARDEN

Whilst the Persian Garden was a strong jumping off point, the project, set in Burquitlam, needed to respond to the surrounding context and flora. The team began to look to modern gardens as a point of reference that emulated many of the same concepts which defined Persian gardens but were actualized through different design approaches. Two very local projects were studied:

KPMB / Hotson Bakker Architects - Richmond City Hall

Arthur Erickson - Museum of Anthropology

As you can see, there are elements of symmetry and emphasis on water that feel similar to the previous Persian examples.

Another beautiful precedent we looked at was Vladimir Djurovic’s Aga Khan Park in Toronto. In particular, this project has crisp edges, defined hard and soft-scapes, and formal organization which aligned with the architect and landscape designer’s initial vision.

THE BORROWED GARDEN

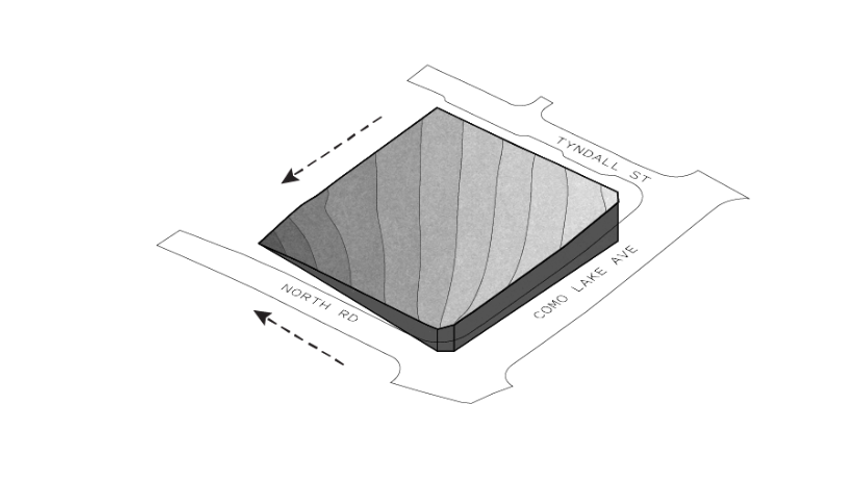

There was another factor to consider: the extreme sloping nature of the site became an undeniable condition that needed to be addressed through considered design. The first way was to take advantage of the slope and extend one’s vantage point beyond the site, creating an opportunity for a borrowed view.

This “borrowed view” is seen in the precedent below. The Shugakuin Imperial Villa in Kyoto was constructed originally in 1655-1659, and renown as one of Japan’s greatest examples of Japanese gardening. Though ancient, its principle of using its elevation advantageously, and extending the user’s eye out to the hills beyond, allows the garden to feel infinite. This was used as inspiration in The Ironwood by using the view to Burnaby mountain and the dense vegetation to create an infinity view when looking from Tyndall Street north-westward.

Another example of this borrowed garden technique (beloved by our Director of Architecture, Bao) is the ha-ha (click here for more)

THE WALLED GARDEN

The second way to take advantage of the slope was to use landscape walls to compensate for the grade changes and define the edges of the site. Walls in gardens have been an architectural feature throughout time and culture as seen with a selection of the precedents we studied below:

hedged walls - Vill Gamberaia in Florence

walls to define space and art - Barcelona Pavilion

walls that play with lighting and transparency - Topher Delaney

walls creating intimacy - Shunmmyo Masuno

One precedent that struck the design team was Tadao Ando’s Church on the Water. The way that Ando uses his walls to define the natural surroundings from the disciplined garden and building, and also how the garden walls help mitigate the topography was compelling. For The Ironwood, this precedent helped to inform the balance of privacy for the residents and porosity to its surroundings..

Below is an architect’s sketch of the site plan, see the prominent (highlighted) landscape walls that define the tower and garden.

THE GARDEN AT THE IRONWOOD

While this blog post has been about sharing the journey of the project’s garden design, it would be remiss not to share where we landed. Below is the Landscape Architect’s Site Plan submission to the City of Coquitlam.

Several events and months, meetings and iterations transpired between the garden stages summed up in this post and this final garden layout. But elements remain from each garden “type”. For instance, the symmetrical water feature (Persian and Formal Garden) establishes an axis for someone to look from Tyndall street to North Rd and see the mountains beyond (Borrowed Garden). And even though the City was not fond of using walls to define the edge of the garden, the use of vegetation to create boundary and privacy was reminiscent of the Walled Garden era.

The process of architecture is long, and winding but often our profession shows a perfect end product without divulging the road that led to it. In this blog, we showed a snapshot of the process of developing the garden at The Ironwood: just one small example of the labour, love and learnings we give and gain throughout the months, and years we spend on our projects.

site plan - PFS studio